When COVID-19 crashed into markets in March 2020, silver did something that surprised many people who view it mainly as a hedge against monetary expansion: it plunged sharply. That drop looks at odds with the “money printer” narrative (QE, fiscal stimulus, and fears of inflation), but a closer look shows the crash was driven by short-term mechanics — liquidity, industrial demand collapse, margin calls and the quirks of paper vs. physical markets — while the monetary effects showed up later. Below I explain the sequence and the drivers, and provide sources so you can read deeper.

The crash was first a liquidity event, not a long-term monetary signal

In mid-March 2020 global markets seized up. Investors needed cash immediately and sold whatever they could convert to dollars. Central bank actions to restore market functioning (swap lines, repo operations and emergency facilities) came as markets were already plunging and often after forced selling had begun. In short: the panic to raise cash caused indiscriminate selling across asset classes — including silver — before the Fed’s longer-term QE and balance-sheet expansion could support safe-haven or inflation-hedge flows. Federal Reserve+1

Silver is a “dual-use” metal — half investment, half industry

Unlike gold, a large share of silver’s demand is industrial: electronics, solar panels, medical equipment and other manufacturing uses. When factories shut and demand for industrial inputs fell in early 2020, that removed a major natural buyer of silver at the same time panic selling hit financial markets. The combination amplified downward pressure on price relative to gold, which is overwhelmingly a monetary/investment asset. Data and industry analyses repeatedly show industrial demand as a major component of annual silver consumption. The Silver Institute

Paper silver crashed while physical demand surged — the disconnect widened price moves

One confusing feature of 2020 was that the “paper” silver market (futures and ETF share redemptions) saw violent selling while retail buyers rushed toward physical bullion and coins. This created a divergence: futures prices fell with forced liquidations, but coin premiums rose as dealers ran low on inventory. In other words, paper and physical are linked, but under stress they can move differently because physical supply chains and dealer inventories don’t instantly reprice the futures market. Evidence of unusually strong physical buying and sell-outs of popular coins appeared in March 2020. BullionByPost+1

Margin calls and forced liquidations magnified the sell-off

Margin requirements and forced redemptions were another transmission channel. When equities and other positions tanked, brokers issued margin calls; funds and traders liquidated positions to meet those calls. Leveraged positions in commodity futures — including silver — were prime candidates for sudden selling. That mechanical forced-selling pushes futures prices down regardless of longer-term views about money supply or inflation, and it happened before fiscal and monetary stimulus could fully propagate to markets. Brookings

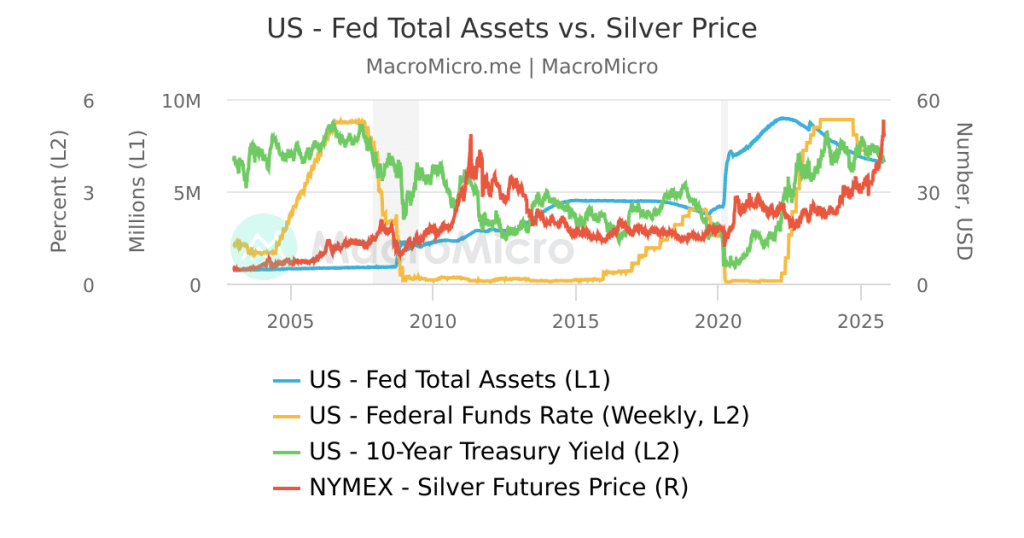

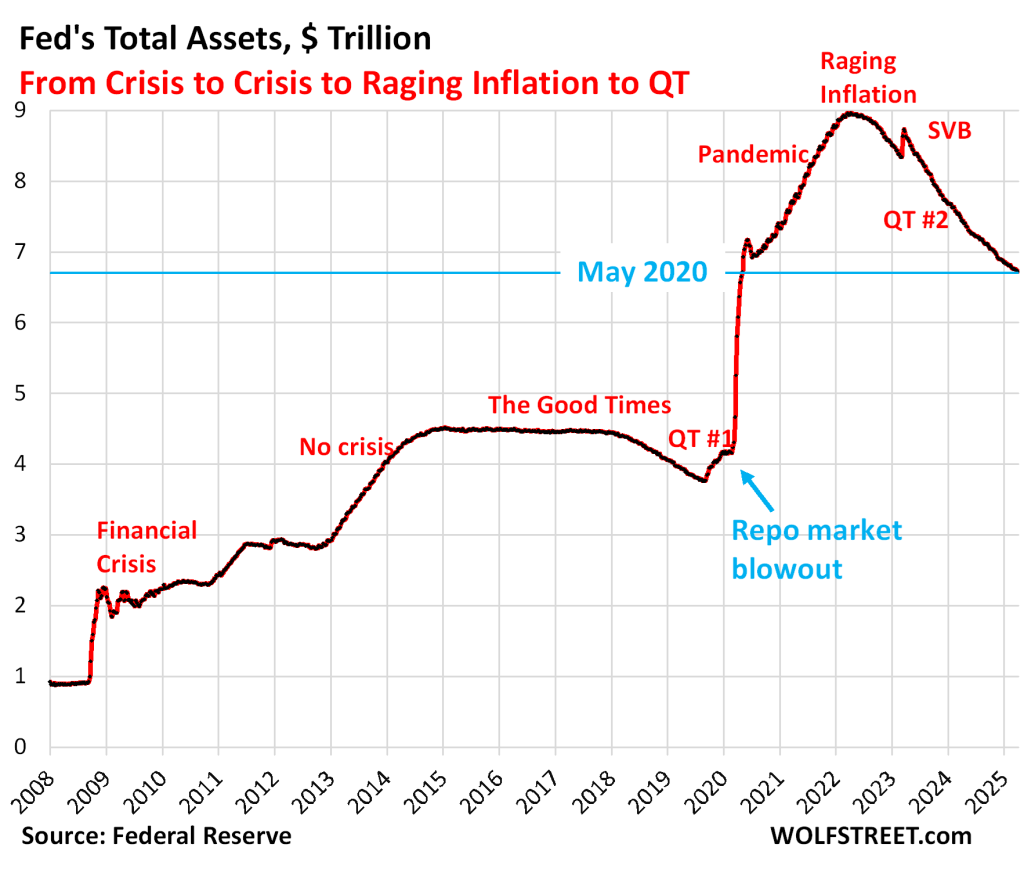

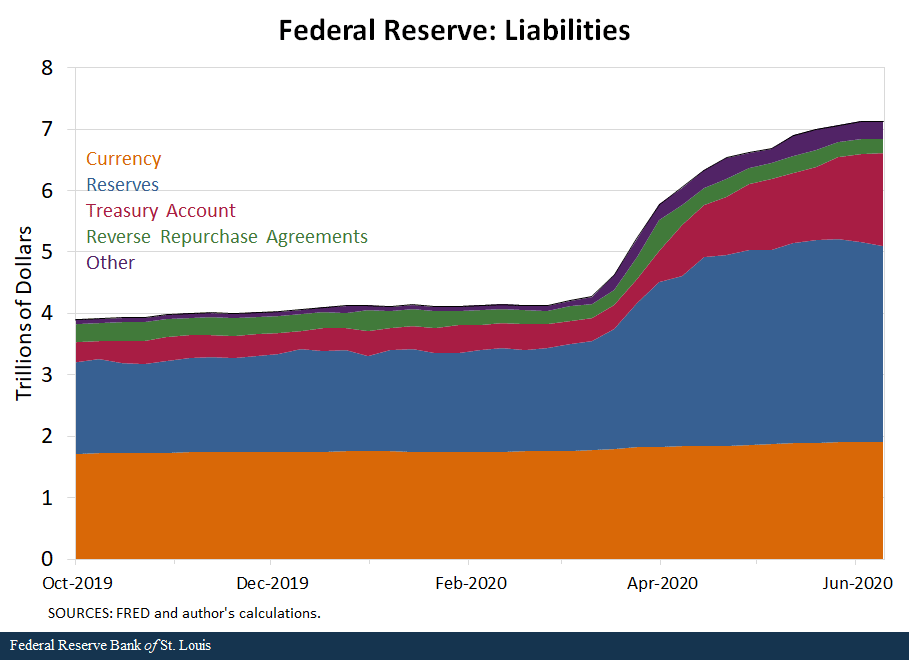

The Fed’s “printing” (QE and balance-sheet expansion) came fast — but its price effects lagged

It’s true that the Fed and fiscal authorities responded aggressively in the weeks after March 2020: massive QE, repo facilities, and large fiscal packages followed. The Fed’s balance sheet expanded rapidly from roughly $4.7 trillion in mid-March 2020 to about $7 trillion within two months as various facilities and open-ended asset purchases were used to restore market functioning. Those actions removed liquidity stresses, lowered real rates and eventually created an environment in which precious metals would rally — but that rally arrived after the initial crash. The timing mismatch (instant panic vs. policy implementation and transmission) explains much of the apparent contradiction. Congress.gov+1

Market microstructure and delivery/backwardation issues

Under extreme market stress, futures markets can display backwardation (near-term prices above deferred prices) or other distortions reflecting acute delivery risk or shortages of physical metal at certain delivery points. These microstructure signals can cause additional volatility and disconnects between spot, futures and physical dealer pricing, and they played a role in the spring and later phases of 2020 when delivery logistics and dealer inventories were strained. Analysts and bullion traders documented elevated premiums and localized strains in physical availability during crunch periods. Sprott+1

What happened next — why silver rebounded

Once liquidity returned — aided by Fed actions, swap lines, and fiscal packages — investors refocused on the macro environment. The combination of near-zero interest rates, unprecedented balance sheet expansion and later concerns about inflation and currency dilution increased demand for monetary hedges and speculative interest in silver. At the same time, as economies recovered and industrial activity resumed, industrial demand for silver improved. Those forces combined to push silver significantly higher later in 2020. The initial crash was therefore a short-term liquidity and industrial-demand shock; the subsequent rally reflected the monetary and recovery story. Brookings+1

Takeaway: two timelines — an immediate liquidity contraction and a slower monetary expansion

If you step back, the apparent paradox resolves into two distinct timelines:

- Immediate (days–weeks): panic, flight to cash, margin calls and collapsing industrial demand — price falls. Federal Reserve+1

- Medium term (months): policy response, restored liquidity, and renewed demand for hedges and industrial goods — price rises. Congress.gov+1

That duality is why silver can both “align” with monetary expansion over the medium term and still plunge during a liquidity-driven crash.

Sources (key references)

- Federal Reserve staff analysis of the COVID-19 crisis and Fed policy response. Federal Reserve

- Brookings overview of the Fed’s March 2020 actions and QE program expansion. Brookings

- Congressional Research Service: Fed balance sheet expansion and policy timeline (spring 2020). Congress.gov

- Silver Institute: supply, demand and the industrial share of silver usage. The Silver Institute

- Reports of physical coin sell-outs and dealer shortages in March 2020 (US Mint / bullion dealers). BullionByPost